There comes a time every year when snow changes both its physical state and its meaning. From a winter deposit, it turns into liquid water, ready to flow downhill. This is the critical transition from accumulation to melt: a seasonal threshold that affects water availability, agriculture, energy production, and ultimately the livability of entire regions. In Italy, April marks the beginning of this shift. It also brings the fifth monthly snow report by CIMA Research Foundation, offering a detailed snapshot of the snow-derived water resource across the country. The data, as always, are clear: the national Snow Water Equivalent (SWE) deficit remains at -34%. Despite this critical figure, signs of recovery are beginning to emerge. It’s a partial rebound—yet a significant one.

A recovery driven by the North

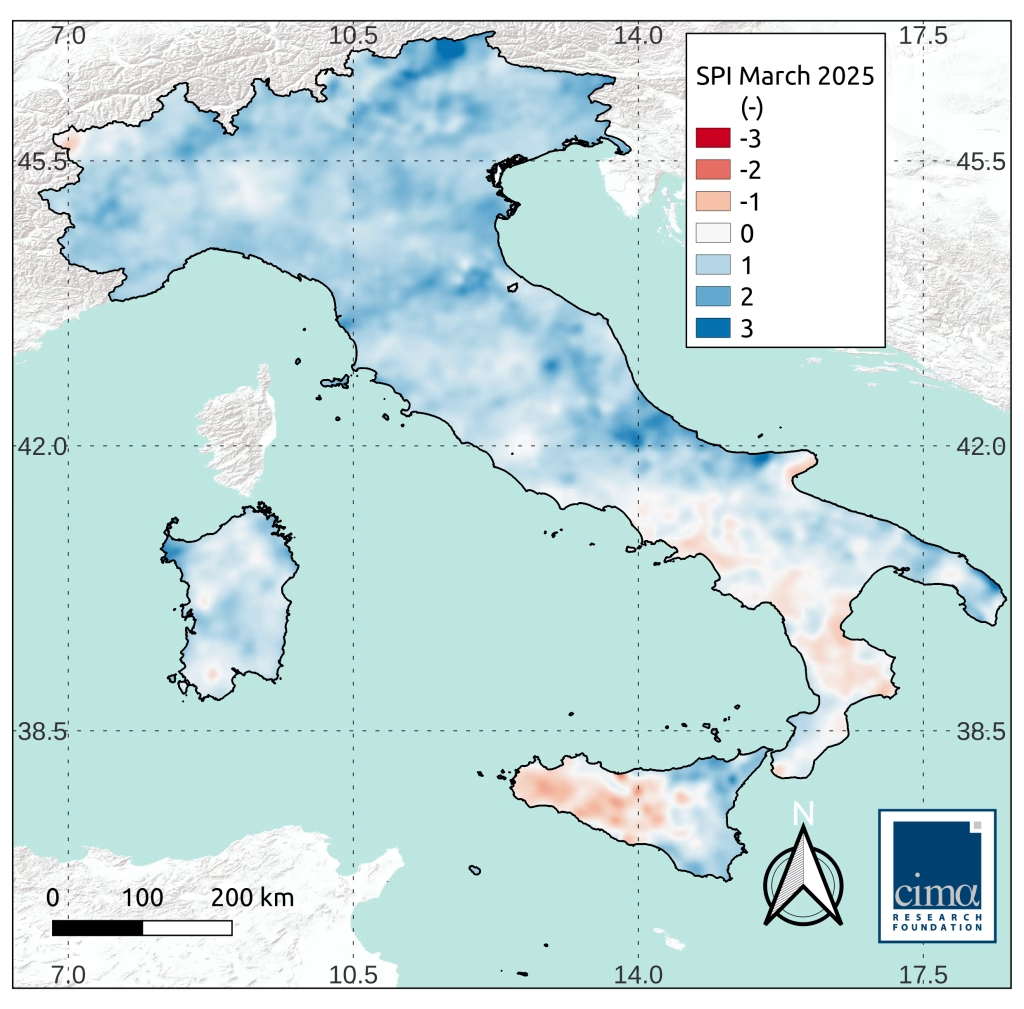

What made the difference in recent weeks was an atmospheric “turnaround”. In the second half of March, most of Italy—excluding Sicily and Calabria—experienced abundant precipitation, accompanied by below-average temperatures, particularly over the western Alps. It was here, in the northwest, that the snowpack responded most effectively. The Alps capitalized on the meteorological window, accumulating fresh snow and reducing the SWE deficit, at least partially.

The Po river basin, the largest in the country and the reservoir of nearly half of Italy’s snow-derived water, currently shows the most favorable conditions: its deficit has dropped to -15%, falling within the range of natural variability observed in recent years. However, the melting season has now begun, and the window for further improvement is narrowing.

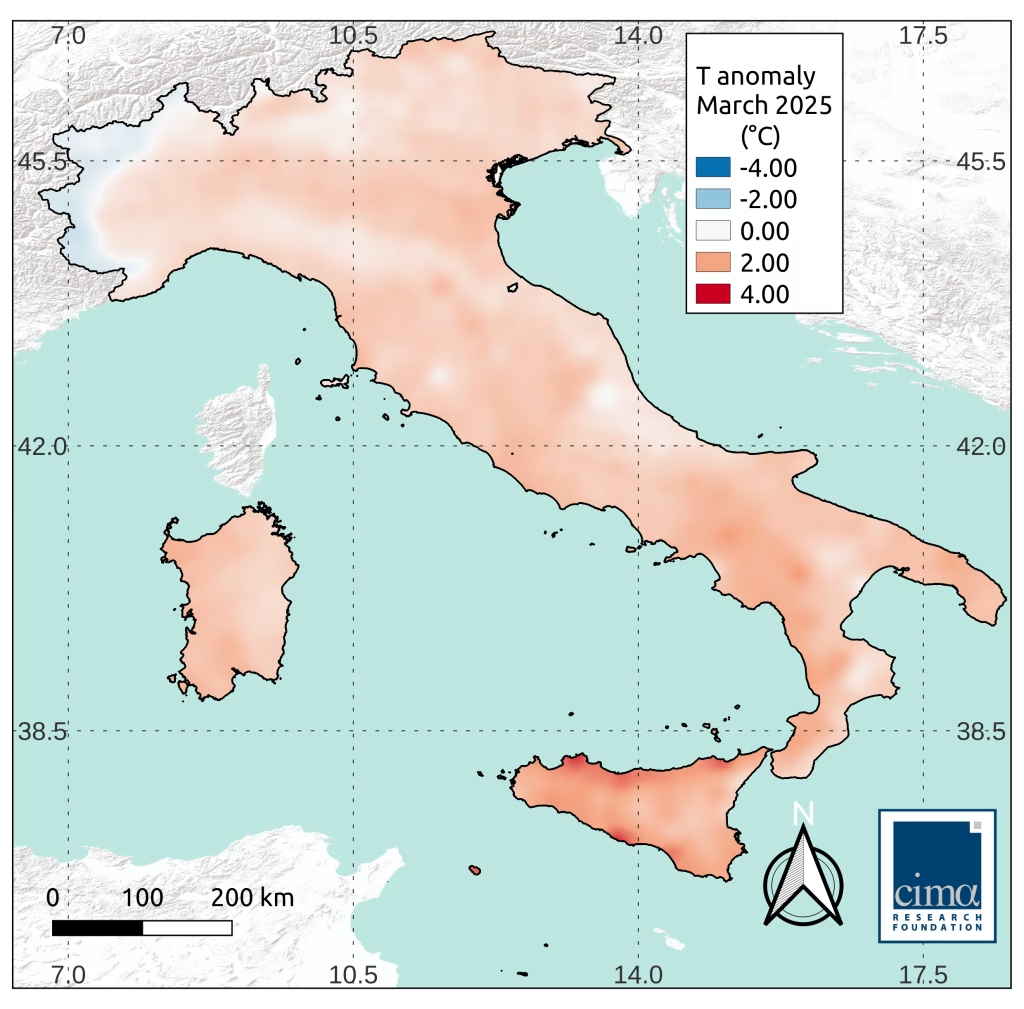

The picture is different in the Adige river basin, where the deficit stands at -37%. Here too, March had brought some recovery, but recent warm temperatures have already triggered early melting, bringing SWE values back down.

“Temperature increases, more than the absence of precipitation, have defined this season so far. In recent years we’ve been witnessing a shortening of the snow cycle: snow arrives late, melts early, and spends less time available to contribute to the hydrological balance,” explains Francesco Avanzi, researcher at CIMA Research Foundation.

Apennines: the weight of absence

The story changes dramatically moving south. In the Apennines, snow is virtually absent at all elevations. One striking figure: in the Tiber River basin, the SWE deficit now reaches -89%. This is a severe anomaly—worse than during the same period in 2024.

The only partial exception is on the Adriatic side, where recent snowfalls led to a slight improvement, particularly in the Aterno-Pescara basin, now showing a -43% deficit. This east-west discrepancy is consistent with the orography and climatology of the Apennine range, but conditions nonetheless remain well below historical averages.

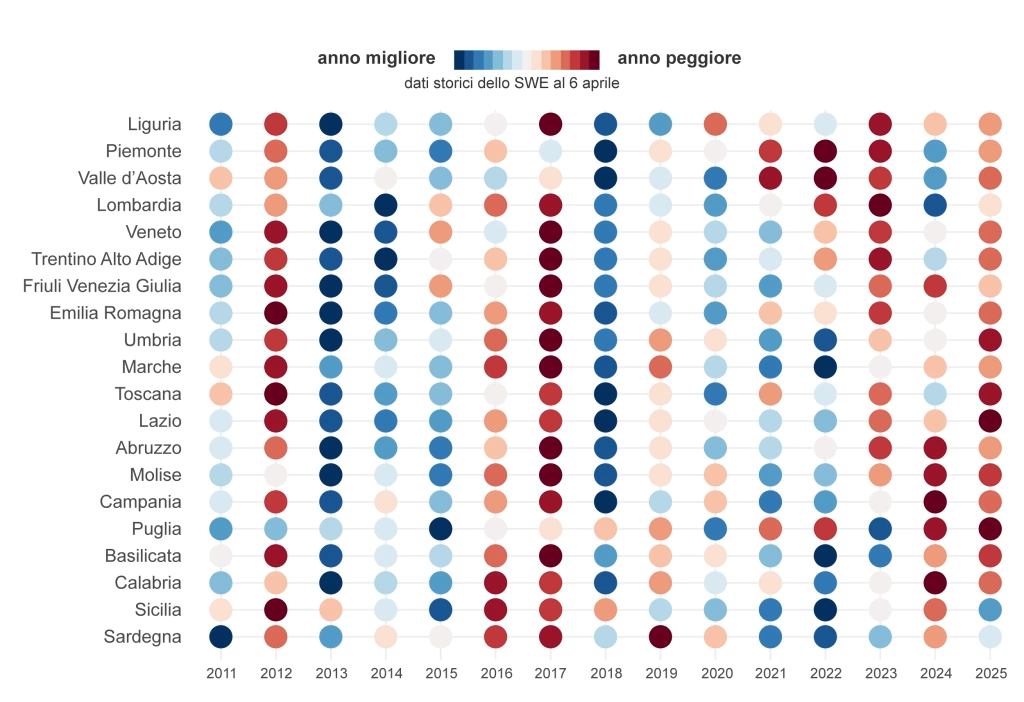

From a seasonal ranking perspective, northern Italy currently sits in the lower-middle range since 2011. The worst year for the northwest was 2022, while 2017 marked the nadir for the northeast. Although the current season has not reached those extremes, it offers little reassurance. In the Apennines, by contrast, this is what we might call the “relegation zone”: one of the poorest snow seasons of the past decade.

Seasonal Forecasts for Italy: looking ahead

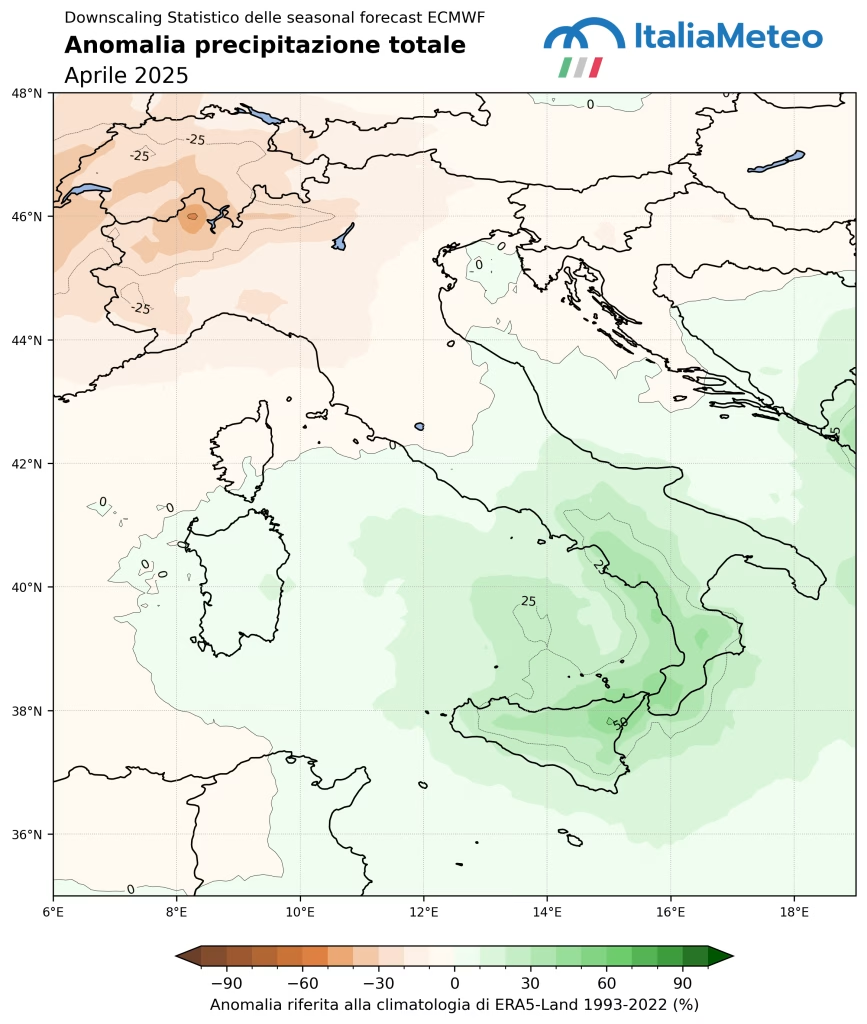

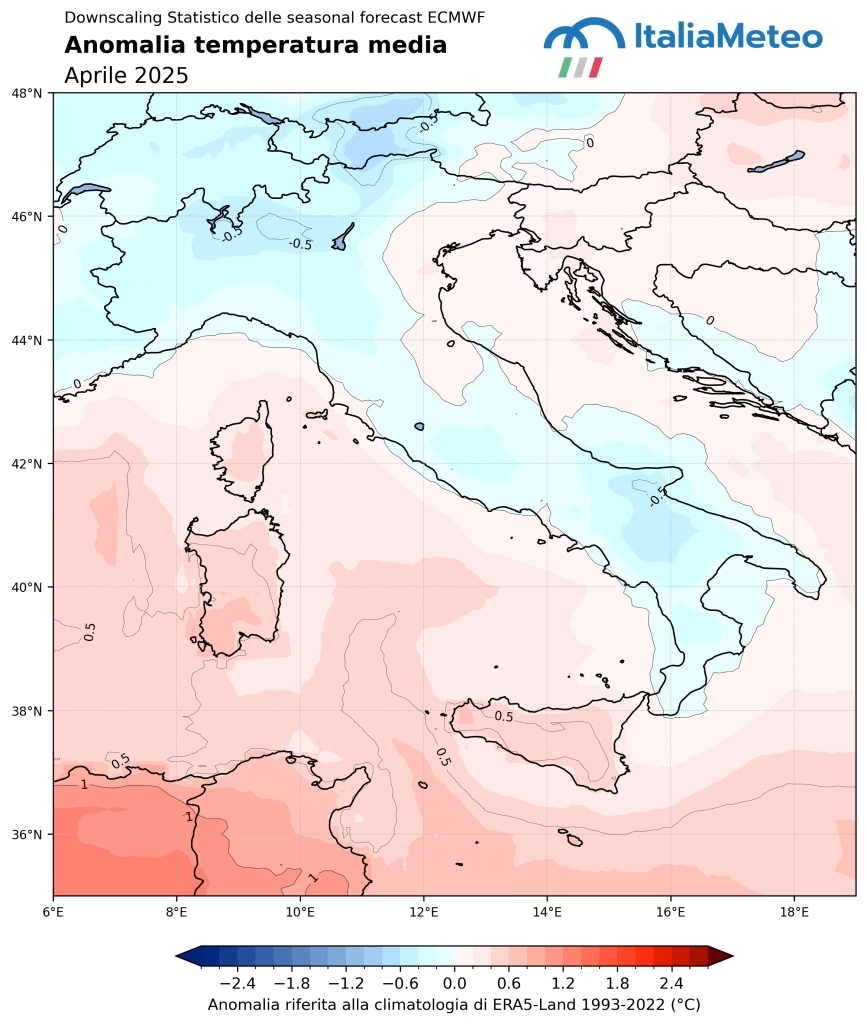

Adding complexity to the picture are the new seasonal forecasts from the national meteorological agency, ItaliaMeteo, available for the first time with country-specific spatial detail1. According to these projections, the remainder of April is expected to be drier than average in the north, and slightly wetter in central and southern regions. Temperatures, meanwhile, are forecast to be cooler than average across the country in April. In the following months, temperatures are projected to rise above the norm nationwide, while precipitation is expected to follow climatological patterns.

In the short term, this suggests a potential deceleration in snowmelt, especially at higher elevations. However, the lack of above-average precipitation in the north—if confirmed—also signals the end of the 2024/25 accumulation season. “When we talk about snow as a water resource, we cannot limit ourselves to the amount of snowfall: it’s the timing and spatial distribution, combined with thermal conditions, that determine its actual hydrological usefulness. A heavy snowfall followed by a rapid temperature rise, for instance, is less effective than a more moderate but stable season,” Avanzi explains.

In summary, this is a transitional season. Snow has fallen—partially. Precipitation has not been entirely lacking. But so far, warmth has been the dominant factor, with above-average temperatures altering the spatial and temporal distribution of snow in many areas. In the coming months, we will better understand the extent of this impact. For now, attention turns to the melt: it is the speed of this process that will determine the actual water availability downstream—and with it, the resilience of the territories.

- Based on ECMWF long-range forecasts, ItaliaMeteo applies a statistical algorithm to increase spatial resolution and calibrate predictions using past data, thereby improving their forecast reliability. ↩︎