The snowfalls in February and March have managed to bring back, for the first time in two years, the Snow Water Equivalent (SWE, the water content in snow) to balance – even registering a slight surplus compared to the median of the last 12 years. However, the situation varies greatly between the Alps and the Apennines, as well as at different altitudes: while in the northern part of the peninsula the deficit has been replenished, especially at higher altitudes with particularly positive values for the Po River, in the south and below 2000 meters above sea level, the deficit remains significant

For the first time in two years, we can say we have really good news regarding snow in our mountains. And consequently, on the water it stores for the warmer months, represented by the Snow Water Equivalent (SWE).

The latest monitoring by CIMA Research Foundation, updated on April 1st, indicates that the national deficit has been cleared. Even better, to be precise, it marks a slight surplus (+1%): the first in two years of observations for this time of the year.

However, what we observed in our last update still holds true: the situation presents significant differences across the peninsula. “SWE data are strongly recovering for the Alps, but still in deficit for the Apennines. As always, the reason for these differences is linked to precipitation and temperatures,” says Francesco Avanzi, hydrologist at CIMA Research Foundation. “This March has been wetter both in the North and Centre of Italy. However, especially in the Apennines, temperatures remained high throughout the winter season. In March, they recorded +2.5°C compared to the last decade. This has led to only little new snowfalls and to an early snowmelt.”

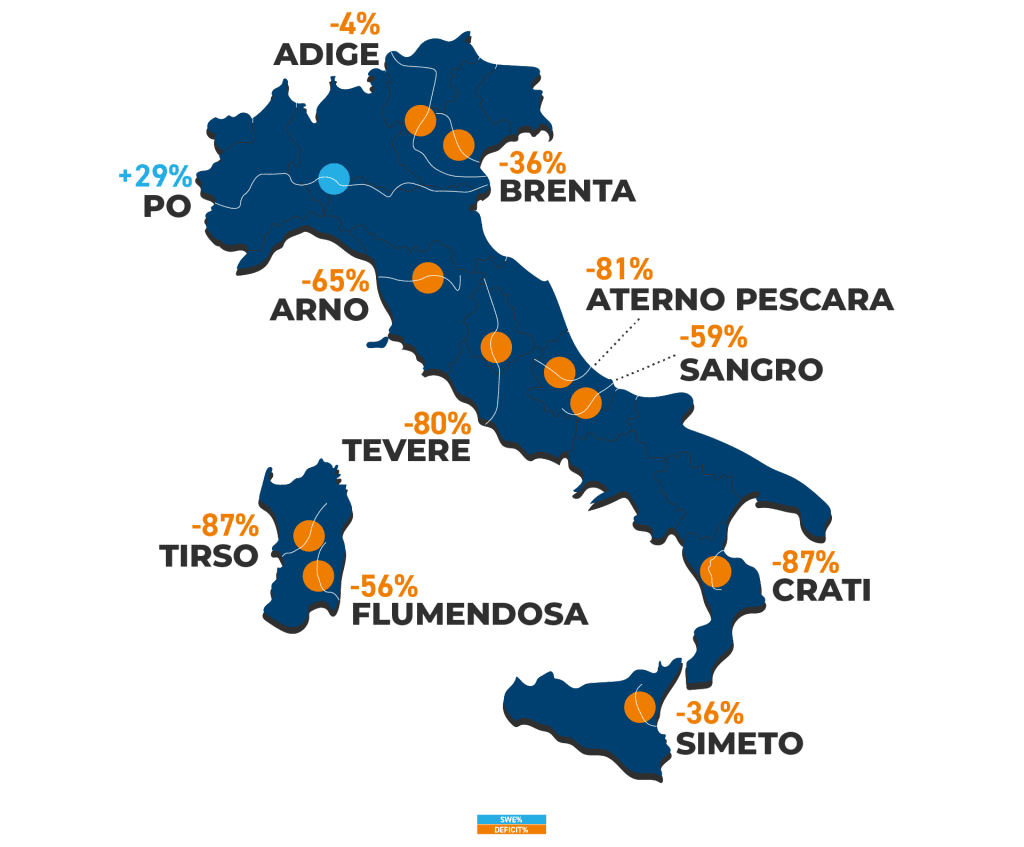

Conversely, in the northern part of the peninsula, in March temperatures remained more in line with those of the last decade. Thus, the abundant precipitation at the end of February and March allowed for a snow accumulation not seen for the past two years. Looking at data for each watershed, the gap is evident: while the Tiber still records a deficit of -80% compared to the historical period, for the Adige the anomaly is just -4%, and for the Po, which has even tripled its snow water resource from February to date, the SWE is up by +29%.

It is important to note, however, that even regarding the Alps, the situation is not uniform, and significant differences are observed depending on the altitude. In fact, the SWE is positive above 1800-2000 meters, where the freezing level has not yet been surpassed. Below this altitude, however, the deficit remains significant. “It’s as if there were two winters at the same time: one snowy at high altitudes, and one with little snow at medium-low altitudes,” comments Dr Avanzi.

The period in which, according to historical data, we can expect the most of snowfalls has now ended. Historically, in Italy, the peak of snow accumulation is recorded in March. We are now in the melting period – when snow begins to turn into the water that feeds our rivers and, along with them, all activities that exploit this resource, from agriculture to hydroelectric power production. “These latest data recorded in the Alps are certainly good news, also because they avoid a critical situation for the third year in a row,” concludes Dr Avanzi. “However, whether and how much the water now finally present in the Po basin can support the spring and summer months depends on temperature. The data showed a significant increase in SWE between the beginning and mid-March, which was about to be followed by a rapid decline, interrupted only by further incoming snowfalls. In other words, high temperatures can still cause early melts, even in the Alps: for it to be truly useful in periods when water is most needed, snow must remain snow for several more weeks.”