A hidden web stretches across the seabed of the southern Tyrrhenian Sea — an invisible network that traps not only fish, but entire ecosystems. Made of plastic bottles, polypropylene ropes, and empty jerrycans, these are Anchored Fish Aggregating Devices (aFADs): artisanal fishing tools designed to attract fish, but which have now become one of the most widespread and under-studied sources of marine pollution in the Mediterranean.

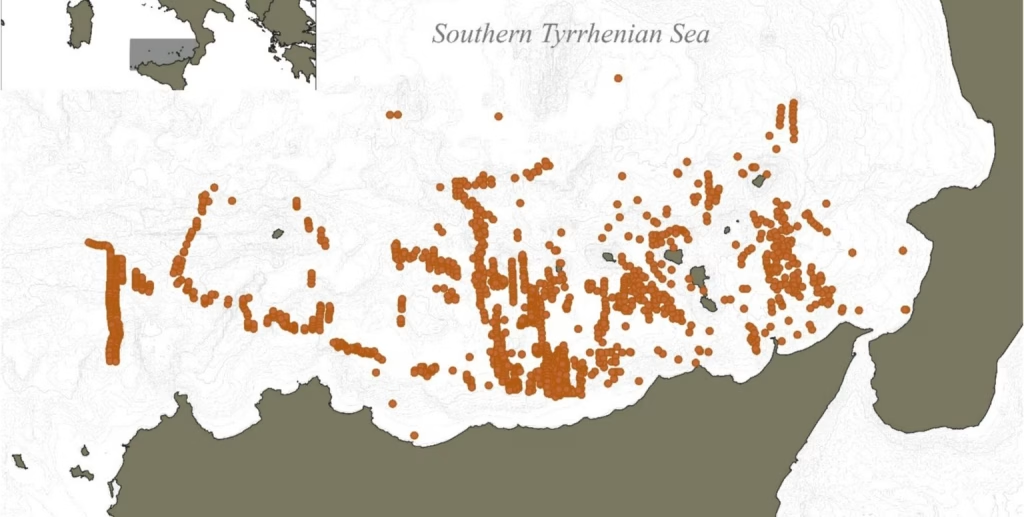

These devices, often abandoned or lost, are anchored with kilometers of synthetic lines that turn into submerged debris — hard to locate, nearly impossible to remove. Between 2017 and 2022, 1,739 still-anchored FADs were recorded in the southern Tyrrhenian Sea during Sea Shepherd Italy’s monitoring campaigns. Adjusted for estimated loss rates in scientific literature, this number likely exceeds 5,500 units in the study area alone.

A strategic collaboration to map the invisible

Unveiling this submerged phenomenon has been possible thanks to a synergy between scientific research and citizen science. Through Sea Shepherd1 missions across the Aeolian Islands and the Calabrian coasts, structured and systematic data were collected and later analyzed by CIMA Research Foundation within the framework of the National Biodiversity Future Centre (NBFC) to produce statistical analyses, distribution models, and environmental impact assessments.

“With the support of the data collected at sea by Sea Shepherd, we were able to create a precise map of the distribution and composition of these anchored FADs,” explains Alberto Sechi, marine ecosystems researcher at CIMA Research Foundation. “The plastic lines alone used to anchor them exceed 2,500 kilometers — roughly the distance between Paris and Moscow.”

Preliminary results of this work were presented in 2023 at the European Cetacean Society Conference as a scientific poster titled The Ghost Labyrinth. Since then, the analysis has continued and was recently published in a peer-reviewed short note, expanding both the spatial and ecological scope of the study.

Impacts on megafauna, habitats, and fish dynamics

The raw density reported in the study is 0.067 FAD/km², which increases to 0.215 FAD/km² when adjusted for loss, covering a marine area of over 25,000 km² — a surface 3.5 times larger than previous estimates. The average anchoring depth is around 1,366 meters, with some reaching beyond 3,500 meters. These FADs, often aligned latitudinally, form real “plastic highways” across ecologically sensitive zones like the cetacean corridor between the Strait of Messina and the Aeolian Islands.

The impact goes beyond the seascape: serious risks for marine megafauna — including turtles and cetaceans — have been documented. Notably, researchers have recently recorded the first confirmed case of cetacean death by entanglement2 in a FAD in the Mediterranean. Additionally, the synthetic materials used — bottles, jerrycans, polystyrene, and nylon ropes — contribute to plastic ingestion in species like the sperm whale (Physeter macrocephalus), which is already listed as Endangered on the IUCN Red List3.

Deep-sea habitats are not spared either: ballast stones and anchoring ropes alter the seabed, damaging corals, sponges, and benthic organisms4, further weakening ecosystems already under stress from climate change and human activity.

“These devices are designed to attract fish, but they also attract problems,” Sechi adds. “If left on the seabed, they become true ecological traps, with consequences that go far beyond fishing.”

Plastic on the seafloor: a legal grey area

From a regulatory standpoint, the use of anchored FADs is only partially addressed. While a 2020 note from the Italian Ministry of Agriculture (MiPAAF, No. 10385) recommends the use of biodegradable materials, this recommendation has no binding legal status and conflicts with the broader European framework, which merely promotes good practices without enforcing them. In fact, only 4% of the analyzed devices contained biodegradable components; all others were entirely or partially plastic-based.

Internationally, agreements like MARPOL5 prohibit the intentional dumping of plastic waste into the sea, but do not address indirect impacts related to FAD usage. Similarly, the recommendations from the General Fisheries Commission for the Mediterranean (GFCM) — which foresee a transition to biodegradable materials by 2027 — remain non-binding.

Currently, fully biodegradable aFADs are not yet commercially available, especially for ballast and anchoring lines. As a result, the most effective and immediately implementable strategy to reduce environmental impact remains a substantial reduction in the number of FADs deployed.

International recognition for a growing issue

The significance of this work has not gone unnoticed. The BBC recently featured this investigation in a long-form report titled “The illegal web of fish traps in Italy’s Mediterranean”, highlighting the key role played by the collaboration between Sea Shepherd, NBFC, and CIMA Research Foundation in unveiling the scale and impact of these submerged devices. “Using statistical analysis,” the BBC reports, “Sea Shepherd has been producing maps since 2017 to identify for the first time the extent of this ghost labyrinth created by FADs anchored to the seabed.”

Reduce, replace, recover

The scientific conclusion is clear: a significant reduction in the total number of FADs is currently the most effective strategy to mitigate environmental harm. Although biodegradable alternatives are highly desired, they are not yet available in fully efficient forms — especially for anchors. Incentives, binding regulations, recovery programs, and, above all, a new culture of sustainable fishing are urgently needed.

The invisible maze enveloping the Mediterranean seafloor can be dismantled. But doing so will require data, shared actions, and a long-term vision for the future of the ocean.

- Founded in 1977, Sea Shepherd is an international non-profit organization whose mission is to stop the destruction of marine habitats and the slaughter of wildlife in the world’s oceans, in order to conserve and protect ecosystems and species. ↩︎

- Entanglement refers to the accidental entrapment of marine animals (like cetaceans and turtles) in ropes, nets, or other floating or submerged materials, which can cause severe injuries or death. ↩︎

- The IUCN Red List is a global classification system for the conservation status of species, maintained by the International Union for Conservation of Nature. The Endangered category indicates a species faces a very high risk of extinction in the wild. ↩︎

- Benthic organisms are species that live on or in the seafloor, such as sponges, corals, starfish, and marine worms. They play a vital ecological role in aquatic ecosystems. ↩︎

- MARPOL is an international convention for the prevention of pollution from ships. It prohibits the intentional discharge of plastics at sea but does not specifically regulate indirect impacts associated with devices like FADs. ↩︎